Forecasts suck. I want to be a weatherman. Who doesn't want to get paid stupid fat amounts of cash to let people like me know that "there's a 50% chance of measurable precipitation, intermittent showers with chances of snow throughout the day and sunny spots in between. "

No lie, that's the weather report I got one morning last week. What kind of weather report is that? Why doesn't this meteorologist, or whatever they call them, just tell me that he "hasn't got a fekkin' clue what's gonna come out of the sky today," but not to worry, cause he "makes truckloads more money than I do"?

Anyhow...

fuck the forecast. I've got a Dreamcast. Many of you may not know what a Dreamcast is, and those of you who do know, prolly wonder why I'm messin' round with such a relic. I bought this little gem off my buddy James, (who picked it off his brother when he heard I was lookin for one) for thirty bucks. And I've never been happier.

fuck the forecast. I've got a Dreamcast. Many of you may not know what a Dreamcast is, and those of you who do know, prolly wonder why I'm messin' round with such a relic. I bought this little gem off my buddy James, (who picked it off his brother when he heard I was lookin for one) for thirty bucks. And I've never been happier.After the Genesis (Mega Drive in Japan,) Sega Corp. became absolutely notorious for producing video game consoles, marketing the shit out of them, and then abandoning them before a decent amount of games had been produced.

It can't all be blamed on Sega, I suppose. The video game market has changed dramatically over the last 3 decades. Those of you old enough to remember, (it's a bit foggy, even for me) the Atari domination of the home console market in the late 70's/early 80's ran challenged only by Coleco, and it's arcade emulating Coleco Vision.

Though the Coleco Vision cannot be blamed for the relative decline of Atari's dominance, the system's superior graphics, sound, and ability to allow owners to emulate and play Ata

ri games certainly ushered in the end of the Atari's regime.

ri games certainly ushered in the end of the Atari's regime. Regardless, both companies fell ill to the video game crash of 1983, when the majority of home console game producers went bankrupt, and the market hit the bricks in North America and Europe.

The perpetual resilience of the Japanese video game market weathered the storm of this crash, and in the early 80's Sega began releasing it's first round of home consoles, initially to compete with the American company, Atari. They started with the SG-1000, and continued with the SG-1000 Mark II, which had an expanded computer version released. Sega's first breakthrough in North America, however, came with the release of the SG-1000 Mark III. On this side of the pacific, it was called the Sega Master System.

Its breakthrough was partially ushered in by the phenomenal success of the "little grey square box" by that century-old Japanese playing card manufacturer, and producer of the Coleco Vision pack-in game "Donkey Kong." Nintendo's Shigeru Miyamoto, now a legend in the video game industry, hit it big with the little plumber running through a construction site, and Japanese "Family Computer," (Famicom as it came to be known) was redesigned and released in North America as the Nintendo Entertainment System, (NES,) and the 8-bit wars were to begin.

Technically, Sega's Master System was superior to the NES. It produced more colours, displayed them faster, and had more advanced sound capabilities. Many remember the motorcycle game Hang On, as a staple SMS showcase. Even more, hopefully will remember Space Harrier, who's superb graphics and prototype first-person style shooting structure rivaled even its  16-Bit Genesis sequel.

16-Bit Genesis sequel.

With both of these systems revitalizing the home video game industry, a flurry of games were released and a myriad of third-party game developers flocked to both Sega and Nintendo to put out their newest release.

Aiming to surpass even Atari's level of hegemony nearly a decade prior, Nintendo began to embark on a series of questionable strong arm tactics. The most notorious in particular, was Nintendo's attempt to deny distribution rights to any major North American retailer who insisted on carrying anything other than just Nintendo products. This created a bit of a stir in the late eighties, but amounted to very little by 1988 when Sega launched its new 16-bit Mega Drive in Japan. A year later, the same system, re-titled as the Genesis, hit store shelves in North America.

The jump to a 16-bit processor produced superior results over 8-bit predecessors, immediately apparent to gamers. Sega got the jump on Nintendo with the Genesis, and enjoyed virtually unchallenged next-generation game sales for nearly two years. Sega's only contender during that time was in NEC's PC Engine, or TurboGrafix 16, as it was titled in North America. Though the PC Engine did well in Japan, (interestingly attributed to the abundance of erotic games released for it there) it failed to fully take off in North America. Part of its inability to successfully challenge Sega was its near exclusive distribution by the corner-shop style electronics outlet, Radio Shack. Though the TurboGraphix 16 was superior to the Sega Genesis technically, it was never able to command the near cult status and following it had achieved in Japan.

Once the Compact Disc age ushered in an awkward arrangement of CD ad-ons and rediculous full-motion-video flops, NEC's North American ad campaign for their new TurboDUO became aggressive and quite bizarre to say the least.

Along with Philips and their CD-I, Sega jumped on the CD bandwagon with their initially $400 cdn. priced Sega CD. Many pinpoint the beginning of Sega's decline as a home console manufacturer at the release and poor support of the Sega Saturn. I would place it much earlier, however, with the investment and loss attributed to the initial CD game generation. The vast storage allowances and low production costs of compact discs proved an enticing sinkhole for a few game companies in the early to mid nineties. CDs in these days, however, were read only, and for the most part, technology hadn't advanced to the stage where game developers could figure out how to incorporate the new video capabilities with real interactive gameplay. The result was that Sega CD and TurboDuo, and particularly Philips CD-i owners could expect to watch games with an abundance of overly pixilated video cutscenes... but rarely get to play them. Most gamers chose to simply watch movies instead, and third-party developers fled the CD scene.

Nintend o weathered the storm and even prospered by ironically, resisting the technological change. They did flirt with the idea of a CD add-on to the N64, and even released a limited number in Japan. It only operated, however, with a mandatory subscription to Nintendo's own in-house internet service, and although the system had some impressive technological capabilities, it never took off. Nintendo's stubborn attachment to production-pricey cartridges saved them the embarrassment of the full-motion-video phase of the industry. Many argued later, however, that this same conservative approach cost them dearly as Sony, Sega and Microsoft eventually figured out how to use CDs, Gds, and even DVDs successfully.

o weathered the storm and even prospered by ironically, resisting the technological change. They did flirt with the idea of a CD add-on to the N64, and even released a limited number in Japan. It only operated, however, with a mandatory subscription to Nintendo's own in-house internet service, and although the system had some impressive technological capabilities, it never took off. Nintendo's stubborn attachment to production-pricey cartridges saved them the embarrassment of the full-motion-video phase of the industry. Many argued later, however, that this same conservative approach cost them dearly as Sony, Sega and Microsoft eventually figured out how to use CDs, Gds, and even DVDs successfully.

16-Bit Genesis sequel.

16-Bit Genesis sequel.

With both of these systems revitalizing the home video game industry, a flurry of games were released and a myriad of third-party game developers flocked to both Sega and Nintendo to put out their newest release.

Aiming to surpass even Atari's level of hegemony nearly a decade prior, Nintendo began to embark on a series of questionable strong arm tactics. The most notorious in particular, was Nintendo's attempt to deny distribution rights to any major North American retailer who insisted on carrying anything other than just Nintendo products. This created a bit of a stir in the late eighties, but amounted to very little by 1988 when Sega launched its new 16-bit Mega Drive in Japan. A year later, the same system, re-titled as the Genesis, hit store shelves in North America.

The jump to a 16-bit processor produced superior results over 8-bit predecessors, immediately apparent to gamers. Sega got the jump on Nintendo with the Genesis, and enjoyed virtually unchallenged next-generation game sales for nearly two years. Sega's only contender during that time was in NEC's PC Engine, or TurboGrafix 16, as it was titled in North America. Though the PC Engine did well in Japan, (interestingly attributed to the abundance of erotic games released for it there) it failed to fully take off in North America. Part of its inability to successfully challenge Sega was its near exclusive distribution by the corner-shop style electronics outlet, Radio Shack. Though the TurboGraphix 16 was superior to the Sega Genesis technically, it was never able to command the near cult status and following it had achieved in Japan.

Once the Compact Disc age ushered in an awkward arrangement of CD ad-ons and rediculous full-motion-video flops, NEC's North American ad campaign for their new TurboDUO became aggressive and quite bizarre to say the least.

Along with Philips and their CD-I, Sega jumped on the CD bandwagon with their initially $400 cdn. priced Sega CD. Many pinpoint the beginning of Sega's decline as a home console manufacturer at the release and poor support of the Sega Saturn. I would place it much earlier, however, with the investment and loss attributed to the initial CD game generation. The vast storage allowances and low production costs of compact discs proved an enticing sinkhole for a few game companies in the early to mid nineties. CDs in these days, however, were read only, and for the most part, technology hadn't advanced to the stage where game developers could figure out how to incorporate the new video capabilities with real interactive gameplay. The result was that Sega CD and TurboDuo, and particularly Philips CD-i owners could expect to watch games with an abundance of overly pixilated video cutscenes... but rarely get to play them. Most gamers chose to simply watch movies instead, and third-party developers fled the CD scene.

Nintend

o weathered the storm and even prospered by ironically, resisting the technological change. They did flirt with the idea of a CD add-on to the N64, and even released a limited number in Japan. It only operated, however, with a mandatory subscription to Nintendo's own in-house internet service, and although the system had some impressive technological capabilities, it never took off. Nintendo's stubborn attachment to production-pricey cartridges saved them the embarrassment of the full-motion-video phase of the industry. Many argued later, however, that this same conservative approach cost them dearly as Sony, Sega and Microsoft eventually figured out how to use CDs, Gds, and even DVDs successfully.

o weathered the storm and even prospered by ironically, resisting the technological change. They did flirt with the idea of a CD add-on to the N64, and even released a limited number in Japan. It only operated, however, with a mandatory subscription to Nintendo's own in-house internet service, and although the system had some impressive technological capabilities, it never took off. Nintendo's stubborn attachment to production-pricey cartridges saved them the embarrassment of the full-motion-video phase of the industry. Many argued later, however, that this same conservative approach cost them dearly as Sony, Sega and Microsoft eventually figured out how to use CDs, Gds, and even DVDs successfully.Sega attempted to rebound from the Sega CD disaster developing another cartridge based update for the Genesis called the 32X. This addition was marketed as one of the first 32-bit home systems, and was meant to be appealing to gamers who wanted backward-compatibility with the vast array of Genesis titles that had been released. The 32X was nowhere near the astronomical prices of the Sega CD, but it still cost about the same as a brand new stand alone console system would have. Some critics wondered why Sega didn't just develop a standalone system with backward Genesis compatibility, instead of the completely awkward and absurd looking top-end expansion that they finally released.

All three Sega systems, (Genesis, Sega CD, and 32X) assembled together proved quite the sight to say the least.

In the end, consumers chose not to fork out the extra dough for the moderate improvements in graphics that the 32X offered with Sony's new Playstation turning so many heads.

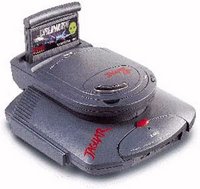

Atari made one brief foray back into the home console industry with their Jaguar, in 1993. Touted as the world's first 64-bit processor, critics often

pointed out that at best, it was a 32-bit system, and may possible fit closer into the 16-bit category, albeit with a few high-powered graphics and sound processors to help the CPU out some. 3 short years saw the commercial obliteration of the Jaguar, and its CD expansion. Its demise primarily ushered in by Sony's Playstation juggernaut, but partially by Sega's Saturn as well.

pointed out that at best, it was a 32-bit system, and may possible fit closer into the 16-bit category, albeit with a few high-powered graphics and sound processors to help the CPU out some. 3 short years saw the commercial obliteration of the Jaguar, and its CD expansion. Its demise primarily ushered in by Sony's Playstation juggernaut, but partially by Sega's Saturn as well.After two relative failure add-ons to the Sega Genesis, followed by third-party hardware cockups like the Wondermega, etc., Sega had a helluva time convincing consumers that they wouldn't abandon the Sega Saturn a couple years after they released it for Christmas 1996.

Their fears were not unfounded. The Saturn, though comparable, if not superior to Sony's Playstation, proved difficult to program for. Sega also proved a difficult company for third-party developers to work with. Many began flocking to Sony, and those who did remain, were outraged by 1998 when Sega began whispering about a new platform altogether. A chain reaction of third-party cancellations began to occur, and in it's final year of North American support, Sega was only able to rustle up a enough five new titles, only one of which was produced by a third-party developer.

And so, it is on the ashes of this dismal failure, that Sega was to embark on yet another. At least by their own standards. As for the international video game community, Sega was about to create what is arguably, to-date, pound-for-pound, the finest video game console ever produced.

Proto-types developed concurrently by a Japanese and an American team, in competition with each other for final release, culminated in the development of a console at least half a decade ahead of its time. In video game years, half a decade isn't quite as long as in PC years, but its still damned close to an ice-age.

The unit's hardware reflected that of a fairly decent PC of the time, a 206 MHz CPU with a 128bit graphics processing unit, the Dreamcast cut through 3D polygons and shading like butter. 4 controller ports came installed directly into front of the unit, no 4-player adapters required. A 33K modem, (later replaced by a 56K, followed by a broadband version) came as a pack in, offering solid online console gameplay as early as 1998 in Japan, and 1999 in North America. (Sony didn't provide an add-on modem for the PS2 until 2002.) Durable, comfortable, analog and digital controllers with intuitive button layout, and a creative controller-based memory card system. The memory units, or VMU's as Sega termed them, were relatively unflattering unless you purchased one with a monochrome gameboy-like LCD screen. These little gems could be plugged into the controller as a regular memory card unit, and then be extracted for portable gameplay related to the game while on the road. This feature was later emulated occasionally

in Nintendo Gamecube titles which worked loosely with later generations of the Gameboy.

in Nintendo Gamecube titles which worked loosely with later generations of the Gameboy.Sega seemed to have learned their programming don'ts from the earlier Saturn debacle by creating a development package which third-party coders found more intuitive. The initial release of games were well-received, and Sega reported sales after the first 24 hours of its launched to have surpassed that of motion picture Star Wars: Episode 1, many times over.

Having teamed up with Microsoft, Sega made the base operating system of the Dreamcast, Windows CE, Bill Gates' operating system of choice for portable handhelds of the day. This made development of non-gaming software possible. A few ideas were tossed around, but the only release most gamers ever saw was the updatable internet browser packed in with the system. Later programs playing MP3 music files, as well as VCD movie discs were released by third-party developers, (some less than legitimately)

The Dreamcast didn't store its games on DVDs like the later Playstation 2 would, partially due to the slow adoption of DVD technology in Japan (VCD and SVCD formats being as available as they were) It didn't use regular; compact discs either, however. Rather GD-Roms were developed specifically for the Dreamcast by Yamaha, allowing both larger storage capacity, and a seemingly hack-proof system.

The hack-proof portion of this format, however, proved particularly short-lived, as media-release groups such as Kalisto and Echelon quickly found ways to rip games from GD-ROMS and burn them on to CD-Rs, which could then be played on the Dreamcast. The explosion of peer-to-peer file sharing allowed such game rip releases to proliferate widely around the Dreamcast gaming community in such a manner that anyone with a CD-burner and some rudimentary know-how could have themselves a decent Dreamcast game collection in no time for the cost of only a few blank discs.

Sega would enter in to negotiations with a few of these hacker groups, and succeeded in buying a few of them out of releasing anything further. By this time, however, the process had become common knowledge, and in some cases, unofficial releases of Dreamcast games were available online before the official release had hit the stores.

Sega attributed their eventual abandonment of the Dreamcast, (staggered from 2000 to 2002 with decreasing support throughout that period) to the proliferation of unofficial game releases, but no substantiation of that claim has ever been made. It's never been clear how many Dreamcast users were able to figure out the process of game download and copying, since it isn't quite as simple as downloading music files and playing them on a CD player. Later releases of the Dreamcast also disabled the unit's ability to read CD-Rs, which threw a wrench into the game copying scene. The unfortunate side effect of this move was that it also disabled the Dreamcast from playing the vast array of amateur games that were beginning to emerge. This roadblock was apparently overcome as well by DC hackers, but after Sega had begun its swansong.

More likely of a cause for Sega's eventual abandonment of the home console market completely, was its lackluster marketing campaign for the Dreamcast after its initial release. Similarly, in perfect Sony fashion, the Playstation 2 marketing campaign began a full year before its release, convincing many gamers to keep their wallets closed long enough to await its launch. Though the PS2 never proved to a be much a technological leap over the Dreamcast, anticipation for it proved fatal. Microsoft's plunge into the market with the XBOX further shook the courage of Sega's marketing execs as they came to realize the size of the other new fish in their pond.

Rumoured to be certain of their inability to wage a prolonged marketing campaign against the two giants who would eventually push even former titan Nintendo into a distant 3rd place forced Sega to pull out of the console market for good.

Fans of the Dreamcast didn't give up so easily, however. The proliferation of downloadable and burned games provided many of them with Dreamcast game libraries larger than anything they would be able to afford on any other system, regardless of the number of third-party developers Sony and Microsoft were able to snipe.

Even Electronic Arts' declaration that they would not support the Dreamcast did little to affect the overall quality of sports titles released on the Dreamcast. The gigantic success of EA's sports series allowed them to build gigantic development centers like the one in Vancouver. A new corporate culture emerged, however, which emphasized quickly produced annual sports titles for profit, over improvements in gameplay. In particular, Sega's NHL 2K series held its own against EA's stagnant reality sports series, and Dreamcast owners were not left missing much.

New leadership at Sega America after the Saturn failure tossed the philosophy that North American gamers "didn't like role-playing games," and thus, groundbreaking games like Phantasy Star Online and Shenmue 1 and 2 were all ported over from Japan. While Phantasy Star Online claims the title as the first console to be played online, and is still played that way by enthusiasts who assembled their own gaming servers after Sega's abandonment, the Shenmue series quite simply changed the way role-playing games were made, and is still regarded as one of the finest gaming advances ever accomplished.

Emulation enthusiasts also began flocking tot he Dreamcast as their system of choice for running old Amiga games and software, SNES, Gameboy, and older Sega ROMS as well. The Dreamcast's ability to play both on a standard NTSC television, as well as a VGA computer monitor (albeit with a relatively inexpensive adapter) increased emulation and video possibilities exponentially.

Additionally a third party memory card with a PC link cable made the storage capacity of the Dreamcast limited only by the size of the gamer's PC hard drive, (an important feature when nearly every game released, and a host of homebrew titles coming out all the time are readily available.)

Only with the release of the XBOX 360 and the soon to be released Playstation 3, is the hardware of the Dreamcast beginning to show its age. Many will likely argue that both of these systems represent a fundamental jump in gaming, period. The XBOX 360, for instance, connects almost seamlessly with Windows Media edition, and in many ways is like another computer. In that, however, is its fundamental weakness. It is, essentially, another computer. There is nothing the XBOX 360 does that a dual core PC processor and a pair of new ATI graphics cards can't churn out

once its coded correctly. The difference with the XBOX, however, is that nearly everything released for it is propriety. Even its online service, XBOX Live comes with its own subscription fee. Microsoft is achieving with its XBOX, what it too a federal Anti-Trust suit to limit them from attaining. And for $700 bucks a pop, one wonders why consumers wouldn't just plunk the cash down for all the other capabilities that come with your run-of-the-mill gaming PC. The Playstation 3 isn't likely to be any cheaper, and depending on which category Nintendo decides to place its new Revolution in, affordable family gaming could be becoming a thing of the past.

once its coded correctly. The difference with the XBOX, however, is that nearly everything released for it is propriety. Even its online service, XBOX Live comes with its own subscription fee. Microsoft is achieving with its XBOX, what it too a federal Anti-Trust suit to limit them from attaining. And for $700 bucks a pop, one wonders why consumers wouldn't just plunk the cash down for all the other capabilities that come with your run-of-the-mill gaming PC. The Playstation 3 isn't likely to be any cheaper, and depending on which category Nintendo decides to place its new Revolution in, affordable family gaming could be becoming a thing of the past.Which brings us back to why the underground gaming scene, and systems like the Dreamcast are so important to the industry, for all the reasons Sega never intended it to be.

3 comments:

Holy shit; longest blog post ever.

I think we can all see where your passion lies.

Drop roofing and Marxism and become a games historian :)

Should approach some electronics magazine with a chapter-by-chapter article on the history of the gaming system as we know it!

Yeah I agree with apollyon about the longest blog post ever. I read it though. Is the Comunnist Manifesto shorter? Man you have to meet Matt from EA. I can't believe you guys haven't met yet. Talk to you soon.

Jaguar also seems to be the first game console that appears to be procrating

Post a Comment